A few years ago, I was hanging out with a close friend, and we were talking about the latest Trump scandal: something awful and racist that he or someone in his camp had said. My black friend turned away from facing me to ask, “Why is it so hard for white people to stop being racist?”

We had forged an agreement around this time to have discussions about race: that any question might be asked, and then answered with the following preamble, “On behalf of all white/black people...” Sometimes this was funny, other times not.

I don’t remember how I answered the question. I might’ve talked for 20 minutes or simply said, “Because we suck.”

But the tone in my friend’s voice haunts me, and probably always will.

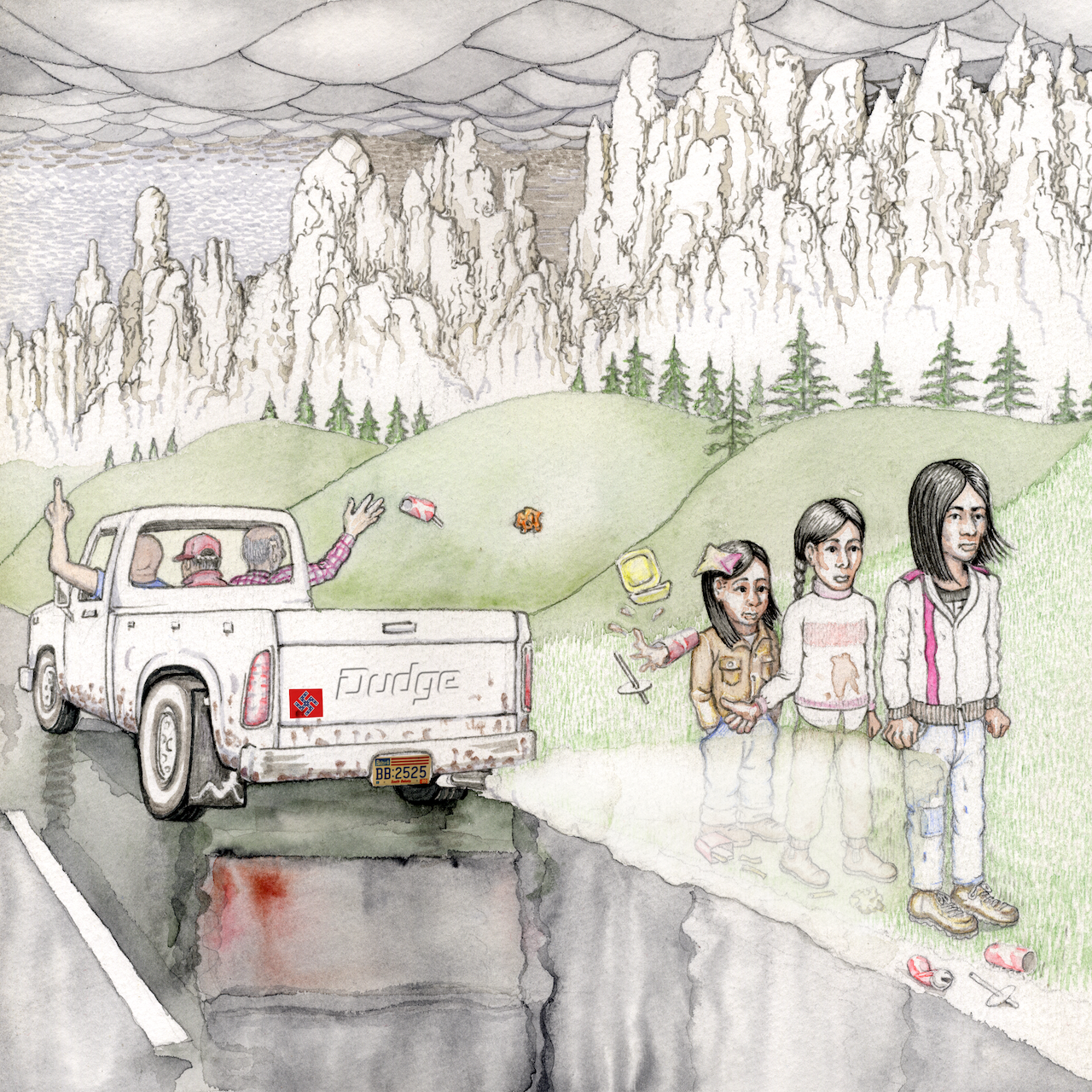

Part 3 of Miss Experience White, “The Other Feast,” is about “othering:” the habit my white tribe has of treating fellow human beings as alien, of less value, and dangerous. Othering is not limited to race, of course. Christians may demonize those of other faiths. Native-born U.S. citizens may demonize naturalized ones. And my experiences as a woman being othered by men have proven helpful in dealing with my own implicit biases toward people not superficially like me.

To try to answer the question, let’s first exclude white people who will take any excuse to be mean to anybody— people who get off on being mean. Let’s also exclude the herd mentality effect, those cowards who go along with the instigators because they get to share in some exercise of dominance. And let’s excuse those who want to be racists, who don’t want to change.

That leaves white people who exist in a culture of white male supremacy, operating with varying degrees of ignorance and denial about that culture. And when faced with our own prejudice, we freak out in varying degrees of intensity. As has been written elsewhere, “To the privileged, fairness feels like oppression.” This manifests as anger, confusion, discomfort, and, for those with some awareness, shame. Oh, our very fragility is upsetting! The description I like best of white privilege is an “invisible, unearned package of assets.” Well, of course, we’re angry, confused, uncomfortable, and ashamed, dealing with something invisible that we did not earn.

The work is ongoing. Anyone who has a chronic mental health issue— alcoholism, depression, etc., knows this means committing to the process and not to the goal. For some personality types, self-monitoring and management can be very challenging. But while humility is not the first value that comes to mind when I think of “American values,” a strong work ethic is, so I remain hopeful.

In the past, I’ve apologized profusely for things I said which I later worried might be racially or otherwise insensitive— only to be affectionately laughed at by the person I thought I’d harmed. (I was still glad I asked.) I’ve also been busted for insensitivities I was not aware of; this is really a kind of frontier of feeling, a new territory. The work is ongoing. Just a few weeks ago I put up a promotional graphic online for Part II, Bonfire of the Ancestors, and was informed that despite my noble intentions and clever efforts it would likely be interpreted as racially insensitive. Down it came.

While doing research for Miss Experience White, I spent a lot of time ruminating over types of privilege and the sometimes awkward remedies of “political correctness.” I got fed up with words. I came up with this handy diagram, illustrated by John H. Seabury, to explain the situation and how there’s no way to avoid negative feelings as long as we’re living in a system of white male supremacy. The deal IS discomfort, and by getting used to it, we get over it, and then move on until a more advanced lesson appears.

To briefly recap a background I’ve written about previously, I was born in 1960 in the San Francisco Bay Area to a father who was a man of his time: admirable and virtuous in many ways but still racist, bigoted, and sexist. My mom was neither a racist nor a bigot, but she freely admitted to not liking women. So my father ruled the household, and, although my mom pushed back on some of his worst language, I still grew up absorbing plenty of toxic talk. Plus, I had to find my own worth as a female. Quite a lot of that work was done while I lived in Los Angeles in the ’80s, 90’s and early 2000’s, and I well remember the few years around 1990 when LA went from being a majority white city to a majority Latino one. I had white friends who openly said that was the reason they were leaving. I thought they were backwards. I lost respect for them

Right now in America, I see two camps. One is consciously ethno-nationalistic, believing they are the “real Americans” because they are white, Christian, and of European descent. The other camp, which I belong to, is diverse with whites in the minority, and although I sometimes feel uncomfortable, this is where I belong. I’m happy here.

What a relief! To paraphrase Chris Rock, America is a less racist country than it used to be. Why? Black people didn’t change, so what happened? White people changed. No reason to stop now.

Milo